In the era of Cyril Ramaphosa, commissions and task teams have emerged as cunning instruments of deceit and diversion, cleverly employed to sway public opinion and deflect attention from pressing issues, writes Professor Sipho Seepe

Asked by 702 radio host Bongani Bingwa last week on whether South Africa’s public health crisis can be solved, Professor Malegapuru Makgoba, the former health ombudsman, replied without hesitation: “I don’t think with this government”.

By any measure, this is a brutal assessment. Makgoba should know. He served his full term as the deputy chairperson of the National Planning Committee after being appointed by President Ramaphosa.

In an article provocatively titled, SA has lots of plans but who is in charge? (Sunday Times, 19 July 2020) Mcebisi Jonas, one of the economic envoys chosen by Ramaphosa came to a similar conclusion. He argued that instead of taking the economy on a positive trajectory, the country is “presented with a multitude of plans, but little sense that anyone is in charge. Debates are often stuck between competing ideological positions rather than developing and driving real productivity and providing jobs.”

Makgoba and Jonas are simply expressing what is common cause that the country is on autopilot and South Africans are on their own. On the other hand, their assessments are a shorthand description of the dysfunctionality that seems to characterise the current administration.

In a widely circulated letter addressed to President Ramaphosa on 31 May, businessman Mike Abel expressed his concerns about the negative impact of the current administration.

“I write you this open letter as a concerned husband, father, businessman, and citizen of South Africa.

“We are in deep trouble and seem determined to only increase the hardship our country and its people face, through the inexplicable decisions by the ANC over the past three weeks, that are taking South Africa to an economic and social precipice.…. As you well know, we currently have crippling load-shedding that sees us without power for up to half a day. Every day.

“It’s near impossible to operate under these conditions alone. But we do. We have no clear answers, solutions, or line of sight as to when this crisis will be resolved. We are now into winter and our people are cold. And they are hungry,” wrote Abel.

The story continues, as Abel presses on with his concerns: “The country is already on her knees. Aside from the power crisis, we have recently seen our crime statistics, rape, and murder rates. Another huge crisis. We have seen our school literacy rates, despite tens of billions of Rands being spent on education, that [aren’t] being implemented properly or effectively.

“We see people dying of cholera from untreated water from plants that are not built or maintained properly…. We see our streets filled with potholes and our railways and stations in tatters due to crime, corruption, and a lack of maintenance or care.”

Instead of focusing on the challenges facing the country, the ANC leadership continues to invest an inconsiderable amount of time and energy in fractious factional battles aimed at purging political opponents. Suspensions, appeals, and expulsion assume prominence to divert attention from grotesque incompetence.

For the likes of Abel, the current crisis is an outcome of “deliberate action. It’s not by accident but by choice.” This is partly true. The second proposition is that the country is led by individuals who stand for nothing, and as a result fall for anything.

For Raymond Suttner, former activist and professor emeritus at the University of South Africa, the problem has more to do with both the ideological and intellectual bankruptcy of the current leadership.

Suttner wrote: “There is little in the record of Ramaphosa to suggest anything more than a self-indulgent, narcissistic attachment to the idea of being president, a presidency that has little content. What ideas, what vision, what ethics, if any, drive this man, and for that matter the organisation that he leads?” (The Daily Maverick, 9 January 2021).

With no ideas of his own, Ramaphosa has mastered the art of obfuscation. He has proved to be unable to give a straight answer to any question. Ramaphosa’s strategy involves skilful deployment of diversion and at times blatant lies. When these do not work, he can always rely on establishing a task team or a commission.

Mmusi Maimane, leader of Build One South Africa could not have described Ramaphosa’s administration better. Maimane quipped. “We are a State of big promises. We’re a State of Commissions, Task Teams, and Road Shows for every possible problem. But when it comes to actually doing things, we are a State of No Action.” (The South African,12 February 2019).

On the appointment of the Minister of Electricity, Ramaphosa said: “It is a challenge that all of us have, and we are addressing it and I’m sure, absolutely certain that having appointed an engineer, a person with deep knowledge about electricity we will be able to solve the problem”.

It didn’t take long before Ramaphosa was contradicted by his appointee, Dr Kgosientsho Ramokgopa. Addressing workers at Eskom Ramokgopa was categoric. “I am not an electrical engineer, I am not a mechanical engineer, I am a civil engineer, we build structures. I don’t know how these systems work. It is you who have studied these things. It is you who understand these operations.”

Constituting meaningless task teams appears to come naturally for Ramaphosa if the Eskom war room that he constituted is anything to go by. The former Group Eskom CEO Brian Molefe had this to say: “The membership of the War Room included people like Professor Eberhardt from UCT, who has never in my presence, uttered an intelligent academic or sane word about electricity or corporate strategy.

“I quickly came to realise that the War Room was not about load-shedding and turning Eskom around. Something else was happening. Eskom senior managers were being destructed from fighting load-shedding by being made to attend endless meetings at which they were supposed to give unending and meaningless reports.”

In those instances where a Commission or task team is fit for purpose, one should not hold one’s breath into thinking that their recommendations would be met. After committing himself to implement the Zondo Commission’s findings, Ramaphosa went ahead to appoint his cabinet ministers and deputies accused of bribery, corruption, and misuse of state funds.

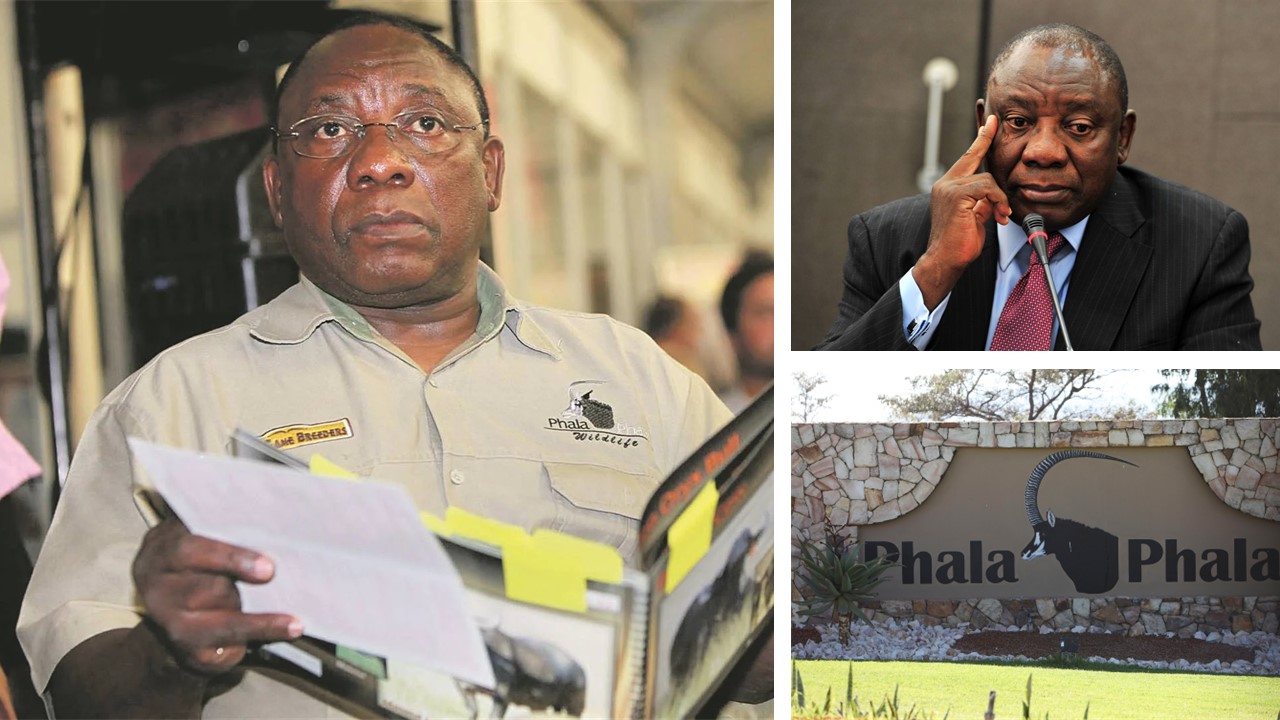

Well, this should not come as a surprise. Ramaphosa once boldly declared that he has a sense of integrity and would step out of the way should his conduct be found wanting. Well, that was before the Phala Phala scandal hit the headlines. We now know that integrity is not one of Ramaphosa’s strong attributes.

All things considered, commissions and task teams have become useful diversionary tools to avoid accountability. It is unfortunate that this dysfunctionality, by design, feeds into the colonial narrative that black rule can only result in chaos. It thus comes as no surprise that we have seen the purging of black talent.

Professor Sipho Seepe is a Higher Education Specialist & Strategy Consultant