Bambihlelo Dikeni Majuqwana voices deep concern over Mcebisi Jonas, a former deputy Minister of Finance, for his apparent lack of understanding of the ramifications of various policy failures, particularly in the context of immigration and border control. Majuqwana argues that Jonas appears overly eager to cater to a liberal political base and prioritize the business interests of the MTN Group, where he currently holds a leadership position.

On October 22nd, 2022, the Kgalema Motlanthe Foundation convened a gathering of influential figures for its annual Drakensberg Inclusive Growth Forum.

The keynote address at the Forum was delivered by Mcebisi Jonas, who previously served as South Africa’s Deputy Minister of Finance and now holds the position of Chairman at MTN Group.

After the meeting, Jonas conveyed his thoughts in an article titled There is a Way: Five Basics To Set South Africa On Course, which was published on timeslive.co.za on October 23, 2022.

Jonas’ suggested “way-outs” can be condensed into the following summary:

•Achieving economic growth;

•Resolving inequality to avert an insurrection;

•Underlying this mistrust is state dysfunction and incapacity.

•Electoral reforms to overcome a crisis of accountability in the state;

•Avoiding popular messianic politics by mobilising a broad front including civil society.

Jonas gave his speech as a representative of the ANC and a prominent figure in shaping public policy.

A lot has happened since the article by Jonas came out. In October 2023, Zionist Israel launched a genocidal war against the people of Palestine under the guise of fighting Hamas ‘terrorists’ in the Gaza Strip. In response to this, and correctly, South Africa has broken off all diplomatic relations with the Zionists.

Israel’s government has decimated Gaza while Zionist settlers are doing as they please in the West Bank, killing Palestinians, destroying their homes and taking their land. There is hardly a doubt that there is more to be gained by South Africa in giving genuine humanitarian support to victims of genocides.

Unfortunately, SA is facing severe resource constraints and is unable to do much in part because of permissive, costly, and illegal immigration practices. Porous borders that fuel social decay, economic instability, and other crimes have compromised the integrity of SA sovereignty. As a result scarce resources are wasted in arresting, imprisoning, feeding, providing hospital care, and educating foreign criminals in our prisons instead of providing support in solidarity for the suffering Palestinian children in Gaza and in other parts of the world.

I find it extremely worrying to find that Mcebisi Jonas, an ex-Minister of Finance, does not appreciate the costs associated with many policy failures, in particular about immigration and border control. Instead the ex-Minister gives the impression that he is too keen to please a liberal political constituency and also to secure the business interests of the MTN Group he leads. His article appears to be a marketing exercise to project his role as a political influencer but not to inform policy development.

Before Russia launched its military operation, the last major crisis was COVID-19 during 2020 and 2021. Almost all countries were affected by COVID-19 and its lockdowns and vaccine mandates. Economies around the world took a big hit and huge amounts of money were spent to secure vaccines from monopoly pharmaceutical corporations to contain the disease. After the pandemic, many countries prepared exhaustive economic recovery plans for COVID-19.

The European Union also launched a Just Energy Transition in line with the prescriptions of the World Economic Forum(WEF). South Africa was recruited to join the energy transition with loans to sweeten its participation but there was no serious COVID-19 economic recovery planning.

Curiously, the lack of an economic recovery plan for COVID-19 does not feature anywhere in the article shared by Jonas. It is a serious deficiency in South Africa’s policy development if leading figures cannot champion national policy but are easily seduced by the faddish thinking of foreign think-tanks as we show in this article.

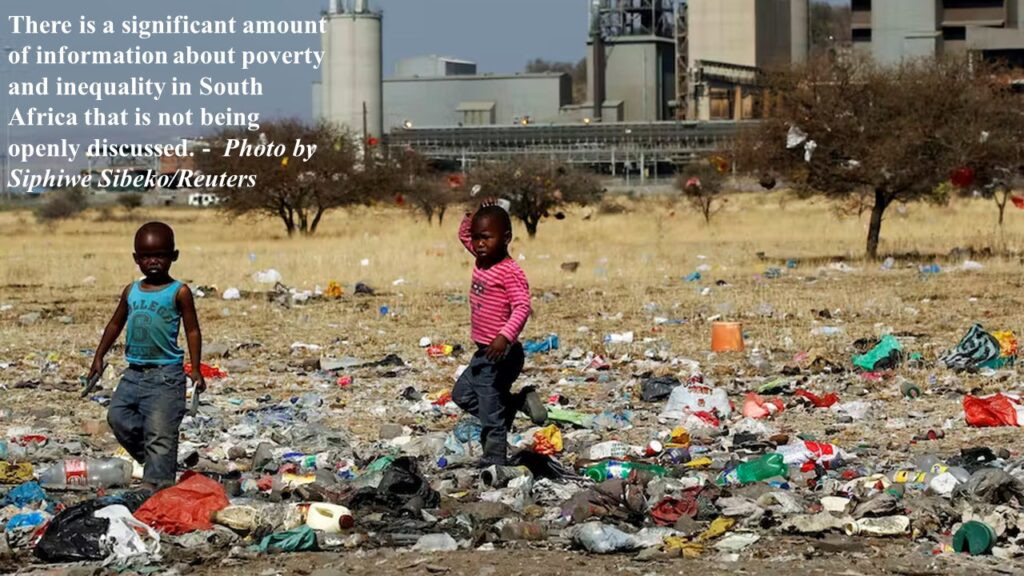

When COVID-19 broke out in 2020 South Africa was already a struggling economy battling electricity shortages. The economy has been in secular stagnation since 2011. A stagnant economy that has been battered by multiple crises cannot sustain a large and uncontrolled influx of foreign nationals, whether legal or not. These are people who come in search of opportunities in competition with natives. Predictably, wages have collapsed in some sectors and capitalists have taken advantage of the illegal immigrants as a source of cheap labour to generate higher profits.

I would like to caution policymakers in South Africa to avoid appearing to be lacking empathy if they believe native workers should not expect their government to prioritise them after the COVID-19 pandemic. South Africa is a country that has always welcomed immigrants but to suggest that it is populism to challenge illegal immigration is to invite failure of leadership. There are laws to regulate immigration. It is these laws or the failure to observe them that must be the subject of discussion as regards illegal immigration.

In any economy, wage stability is as important as that of the prices of other commodities, especially those that the workers depend on. Oversupply in any market destabilises all prices including wages. This is the effect of illegal immigration. It cheapens the labour of the lowest-paid workers, forcing them into deeper poverty and starvation.

My sense is that this is exactly what promoters of illegal immigration want to achieve, to force the native workers into total dependence on the government for easy manipulation of their militant behaviour to avert revolution.

Jonas uses the enticing language of ‘inclusive growth’, ‘financial inclusion’, and ‘investment’ but does not explain what he means by these terms. OECD defines inclusive growth as ‘fair’ distribution across sectors to create ‘opportunities’ for all. UN defines financial inclusion to mean access to “financial products and services” offered by banks, insurance companies, loan sharks, and the like.

Financial professionals talk of investment in an ‘asset’ concerning carrying out activities to increase the value of the asset over time. This is the language of capitalism. Jonas is recruiting us stealthily to see the world in the image of the institutions that own this language: OECD, World Economic Forum (WEF), World Bank, and United Nations.

This is important because it suggests that what Jonas is conveying is recommended or standard thinking by the dominant capitalist narrative according to these institutions. The developmental state has been a theme in policy circles in South Africa for some time, but it appears this is no longer the case.

But Jonas and other politico-corporate influencers are more inclined to trumpet the latest slogans by the WEF than to champion national policy development. That said, the developmental state as a framework for policy advancement cannot be underestimated.

The danger however is to consider it as a fad to be dropped at will. Let us take ‘inclusive growth’ about climate: green growth, just energy transition, and so on. In the first place, this is an agenda item of the WEF, a platform of the world’s dominant corporations that excludes the natives of the various countries of the world.

In the WEF agenda, words like ‘inclusive’ suggest an afterthought and possibly a trick to fool the rest by making it sound exotic. It’s a psychological operation by the Western corporations and the governments they control. In essence, ‘inclusive growth’ is about retaining the status quo by excluding the oppressed.

Similarly, ‘financial inclusion’ is about keeping the status quo of a dependent mass of people in society as a source of profit for the monopoly corporations and their banks.

In 2007/8 there was a Global Financial Crisis that began in the USA. The source of the financial crisis was profit-driven financial ‘inclusion’ in the US via the credit system and the stock exchange to provide housing for the working majority. Society paid for that crisis through bail outs for the banks who have their profits guaranteed by the state.

Therefore, in essence, financial inclusion is about exclusion via selling debt to oppressed people to secure bigger profits for monopoly banks. The idea is to secure these profits in such a way that the oppressed pay for maintaining their own oppression. There is an urgent need for policymakers to critically examine the role of the financial system as an instrument of capitalist oppression.

The point is to pursue reforms of South Africa’s financial policy to create an emancipatory financial system with the banks in the hands of the people according to the policy of the Freedom Charter.

Again, the framework of a developmental state offers rich historical experience in other countries. Ultimately, monopoly banking that developed in South Africa towards the end of the apartheid period up to 1994 must be dismantled. The Western imperialist order that inspired monopoly banking in SA is now in deep crisis.

Therefore, the policy questions and contradictions relating to this must receive the attention of policymakers in South Africa. Investment in the context of ‘inclusive growth’ is also an agenda item of the monopoly corporations subscribing to the WEF.

Again, by “inclusive”, the WEF means exclusive. Within this ‘inclusive’ agenda of the WEF, governments have been recruited to articulate a particular type of investment and entrepreneurial thinking to entrench the dictatorship of the present monopoly financial system, in particular monopoly banks.

To his credit, Jonas recommends social protection by the state because he is aware that ‘inclusive growth’ is a fraud for the benefit of monopolies whose profits are protected by the regulatory policy of the capitalist state. Also, investments in ‘inclusive’ growth are financed by the blood and sweat of the excluded working majority who are legally forced to subscribe to pension contributions for the benefit of the monopoly financial system.

These pension funds are made available to a handful of fund managers dominated by the colonists and imperialists for stock-exchange gambling. Big private equity groups use these pension funds to hunt for asset-stripping opportunities using the debt regime of the financial system.

Curiously, Jonas recommends a strategy of making many small capital investments for his ‘inclusive growth’ as opposed to a few large projects. His reasoning is understandable only if he means investments to maintain the status quo of the existing system, to repair visible cracks in it. But strategy follows policy.

The present regulatory policy regime is what Jonas has in mind. That’s where maintenance belongs for the benefit of monopolies and cartels. The National Development Plan is a policy of the developmental state in South Africa, but it is coming up against the obstacles of regulatory policy. For the NDP to work a few large investments are inevitable but Jonas is clearly blind to this.

We know physical infrastructure is the basis of any economy that is self-sufficient in productive industry as in a developmental state. Manufacturing is the basis of both physical infrastructure and productive industry. Therefore, any viable investment policy necessarily includes a simultaneous decision that includes infrastructure and productive industry.

One without the other will only invite policy failure. Jonas failed to put his finger on this point that the policy of a developmental state leads to a strategy of building productive industry and that this does not discriminate between large and small investments. This is the only truly ‘inclusive’ approach to growth.

On one hand, there is infrastructure that is generally large, extending over distances and absorbing large capital. That is the basis for the few big investments. On the other hand, there is productive industry ranging from many small entrepreneurs and traders to a few large monopolies and cartels that command whole global markets.

Physical infrastructure long-term investments as profit regimes are similarly scaled over large and small time horizons. That is to say, Jonas’s five points reduce to one – oppression of the natives under monopoly capitalism in South Africa and the policy process required to free the people. This is the question that South Africa must fix first before deciding on the superstructure including developmental state institutions, social policy and the question of their governance.

The policy question is how to resolve the conflict between regulation concerning monopoly capitalism and development concerning achieving emancipatory economic conditions as prescribed in the Freedom Charter, to restore wealth to the ownership of the people. Jonas needs no lessons in this as a veteran ANC member, but he must gather the courage to resist being a public influencer for the benefit of the monopolies that oppress the people, in particular the natives in South Africa.

Bambihlelo Dikeni Majuqwana is an independent analyst.