By Avik Jain Chatlani

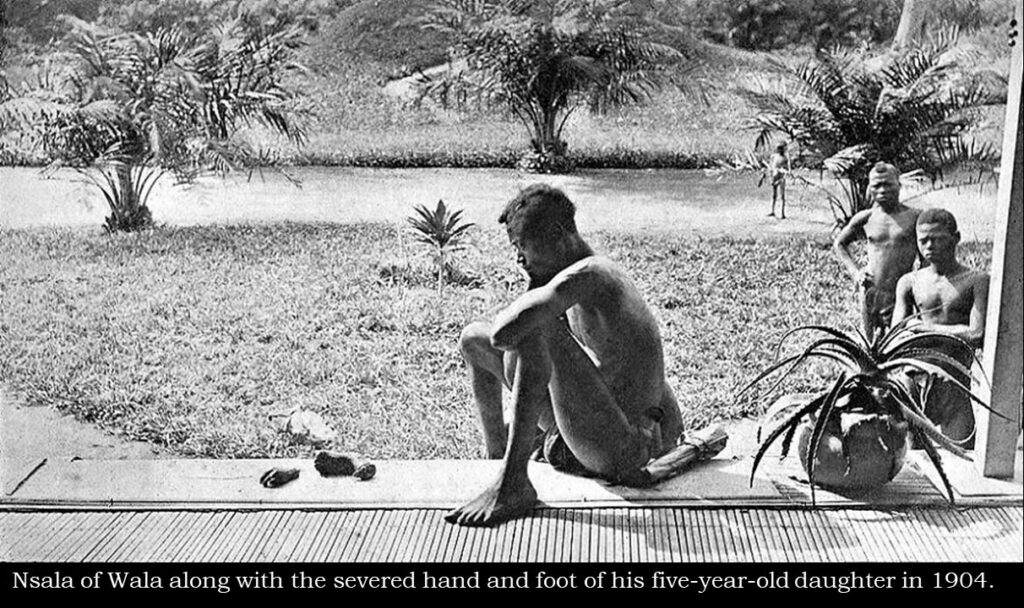

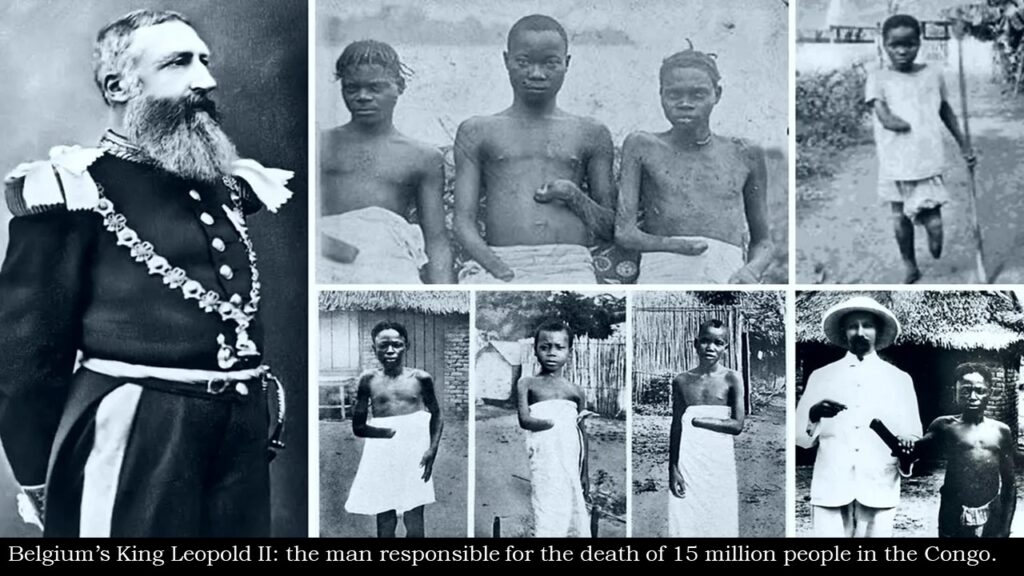

While the Holocaust saw a total of 11 million murdered – both Jews and non-Jews – the Congo saw even more death and destruction. Yet, the genocide of the Congolese people hasn’t even been included in Western curriculums or any curriculums. It hasn’t been erased, it wasn’t even there to begin with.

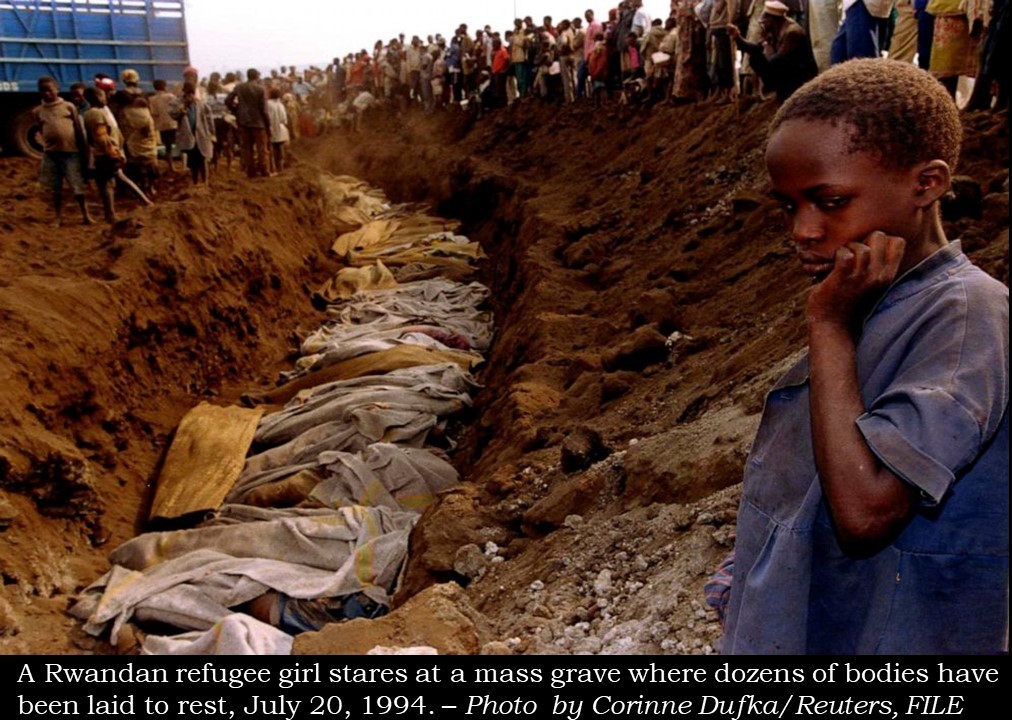

Today, the world continues to rape the country, seeking metals for electric car batteries. But now, as with Rwanda, Cambodia, Darfur, Iraq, and the slave trade, we don’t need a curriculum or a government’s approval to learn about these nightmares.

Everyone can explore the depths of human history, quickly, with an internet connection. Still, for most of those in power, it seems impossible to care about anything other than the 1930s and 1940s in Europe…and perhaps the events in eastern Ukraine since 2022.

When the genocides before and after the Holocaust are ignored – and when the non-Jewish victims of the Holocaust are omitted, as the Israeli lobby is keen on doing – we arrive, exhausted, at Aimé Césaire’s conclusion, which still rings true, especially when you compare the Western response to the invasion of Ukraine versus the ongoing annihilation of Palestine:

“Yes, it would be worthwhile to study clinically, in detail, the steps taken by Hitler and Hitlerism and to reveal to the very distinguished, very humanistic, very Christian bourgeois of the 20th century that without his being aware of it, he has a Hitler inside him, that Hitler inhabits him, that Hitler is his demon, that if he rails against him, he is being inconsistent and that, at bottom, what he cannot forgive Hitler for is not the crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the blacks of Africa.”

Holocaust survivors such as Kertész were able to recognise the exploitation of the Holocaust through kitsch. Many have criticised the Holocaust industry, which churns out books and movies that are error-ridden and insensitive. Worse than the commercialisation is the fact that renowned human rights activists and Holocaust survivors such as Elie Wiesel, never said a word about the Palestinians.

And when you realise that many European settlers gang-raped Palestinian girls for days and days just a few years after the Holocaust ended, during the Nakba, is it possible to conceive of the idea that, for the Israeli rulers and their allies, from the United States to Germany, from Canada to France, the Holocaust has become meaningless?

When an apartheid project uses a historical event to justify its actions – and when that same project builds walls around a people, throws them out of their homes, bans their books, burns their trees, burns their children, carpet bombs their apartment buildings, schools, hospitals, bulldozes their homes, has teenage soldiers strip them, dances on their cemeteries, extinguishes their churches and mosques – the historical event in question loses all meaning. It becomes a brand, a slogan. “Never again.” Never again?

Some, like the brave protestors from Jewish Voice for Peace, have honoured the memory of the Holocaust. They have used their demonstrations to shame the propagandists; they have fought the cruelties of Zionism with the true values of Judaism. Unfortunately, the Zionists, who have no such piety – who target Jews who speak up for Palestinians, who try to banish them from their faith – also happen to have all the institutional power.

But power does not erase truth. Sara Roy – the daughter of Holocaust survivors who lost 100 relatives in the camps – wrote about the parallels between the behaviours that flourished in the Europe of the 1930s and 1940s, and the reality for Palestinians since 1948:

“Standing on a street with some Palestinian friends, I noticed an elderly Palestinian walking down the street, leading his donkey. A small child no more than three or four years old, clearly his grandson, was with him. Some Israeli soldiers standing nearby went up to the old man and stopped him.

One soldier ambled over to the donkey and pried open its mouth. “Old man,” he asked, “why are your donkey’s teeth so yellow? Why aren’t they white? Don’t you brush your donkey’s teeth?” The old Palestinian was mortified, the little boy visibly upset.

The soldier repeated his question, yelling this time, while the other soldiers laughed. The child began to cry and the old man just stood there silently, humiliated. This scene repeated itself while a crowd gathered. The soldier then ordered the old man to stand behind the donkey and demanded that he kiss the animal’s behind.

At first, the old man refused but as the soldier screamed at him and his grandson became hysterical, he bent down and did it. The soldiers laughed and walked away. They had achieved their goal: to humiliate him and those around him. We all stood there in silence, ashamed to look at each other, hearing nothing but the uncontrollable sobs of the little boy.

I immediately thought of the stories my parents had told me of how Jews had been treated by the Nazis in the 1930s, before the ghettos and death camps, of how Jews would be forced to clean sidewalks with toothbrushes and have their beards cut off in public. What happened to the old man was absolutely equivalent in principle, intent, and impact: to humiliate and dehumanise. In this instance, there was no difference between the German soldier and the Israeli one.”

Beyond the daily humiliations that they gleefully engage in, the Israelis have tried – with all their subsidies and bombs and apologists – to erase the Palestinian people. What they have done instead – by flying in settlers from Brooklyn and Kyiv, by trying to sell nuclear weapons to apartheid South Africa, by blaming the Arabs for what the Germans did, by cosying up to the countries that despise Jews, by calling children and disabled refugees Nazis, by shooting autistic boys, by raping Palestinian women and girls, by raining chemical weapons down from the skies and by denying three-quarters-of-a-century of land theft and ethnic cleansing – what they have done instead is erase the Holocaust. They have denigrated it. They have turned suffering into a talking point, a lobbying narrative, a fundraising memo. A dishonouring of memory.

Edward Said wrote that the Palestinians were “the victims of the victims.” However, while Palestinians are certainly the victims, the Israelis are not. The monsters dropping thousands of bombs on Gaza are not victims. They have no ties to victims, they have ceased to be victims, they never were victims. They are genocidaires, nothing more.

This dehumanisation was to be expected. Liberal Zionists such as author Yishai Sarid have grudgingly noted that the young Israelis have been brought up in a culture that teaches them that the victimisation of the Jews of Europe gives them the right to commit atrocities when they grow up. “That’s what we should do to the Arabs,” one of Sarid’s adolescent Israeli characters notes, when he exits a government-sponsored tour of Auschwitz. They’re doing it now, it’s a Google search away. This is the first live-streamed genocide.

I will always remember the children left alone in this world, burned, torn open, flailing in bombed hospitals on my screen. I will always remember the leaders of every so-called democracy, from Canada to the UK, from France to the US, from Germany to India, who cheered it on, who used the crimes of past generations to cover up the war profiteering and massacres of the present. I will always remember every powerful country, like Russia, or China, that staked nothing.

I will always remember how piddling little mayors and university presidents and attorney generals and CEOs prioritised the feelings of those who support genocide, those who smirkingly claimed that they “felt unsafe”, over those who were being subjected to genocide. And I will always remember how they chanted at us in school “never again.”

When I teach again, I may be asked what the point of all this was. What was the point of all this history, all these books, all these stories, all this learning, if they can do this to the Palestinian people?

I could give some answer about memory, or about the need to document. I could abandon history and talk about religion, about faith, or I could cling to action, mention a charity that we can donate to in Gaza, another demonstration we can attend. Or, better yet, I could say nothing.

But what I really want to answer is that I don’t know what the point was. As we all see evil on our screens, in perfect quality, every day, every minute, as we get to hear the voices of the people being killed as they say goodbye to us, I will admit that no words will bring us comfort. No one will be able to say anything or write anything to make it better.

That’s what I will answer. Of course, there are no guarantees that someone will want to know, or that I will be clear-headed enough to reply amidst all of this misery. Fateless ends with a line that tempers my imagined response: “If indeed I am asked – and provided I myself don’t forget.” – newarab.com

Avik Jain Chatlani is an author and historian.